Making of Zabriskie Point

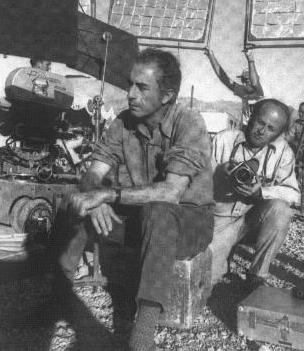

Zabriskie Point was to be Michelangelo Antonioni’s greatest triumph, a crowning achievment in an already seminal body of work and a bold affirmation of his commercial ascendance in America. It was to be the Italien-born director’s state-of-the epoch adress, a provocative document of the political injustice, civil warfare, and extreme moral and cultural polarities defining the end of the 1960s. The eagerly awaited successor to Antonioni’s stunning 1966 succes, Blow Up, a stylish mystery and enigmatic study of naivete and ennui in swinging, pop-art London, Zabriskie Point was to be nothing less than Antonioni’s portrait of the United States - and by extension, Western society - at war with itself.

It was to be a film made with the kind of financial largess, technical facilities, and corporate indulgence that only a major, old-school Hollywood studio like MGM could sanction.

But just about everything that could go wrong with the project did go wrong, and Antonioni’s great dream would prove to be his worst nightmare. Released in March 1970 after nearly two arduous years in production - a period that included long, exhausting shoots on location in the California desert, pitched battles between Antonioni and MGM executives, and a protracted, frustrating search for the perfect musical score - Zabriskie Point was one of the most extraordinary financial disasters in modern cinematic history. The arithmatic alone was astonishing.

Reeling from severe management trauma yet eager to capitalize on the booming counterculture youth market, MGM - which went through three presidents during the production of Zabriskie Point - poured $7 million into the film, an extravagant figure for that time and nearly five times what Antonioni spent to make Blow Up (the first release in Antonioni’s three-picture deal with MGM) had taken in more than $20 million at the box office, Zabriskie Point made less than a tenth of that - a mere $900,000 - in its brief theatrical run.

For the 58-year-old Antonioni, Zabriskie Point was a calamity of a more serious and personal nature. His first feature film to be made in America - where Antonioni first became a celebrated figure for his early and mid-60’s works L’Avventura and Il Deserto Rosso - Zabriskie Point was also the director’s first big flop and provided a crippling blow to his artistic reputation. Critics of all ideologies - establishment, underground, and otherwise - greeted the movie with howls of derision. They savaged the flat, blank performances of Antonioni’s handpicked first-time stars, Mark Frechette and Daria Halprin, and assailed the script’s confused, unconvincing mix of hippie-buzzword dialogue, self-righteous, militant debate, and free-love romanticism.

Today, free of the heavy air of debacle that haunted the film at its release, Zabriskie Point can be seen as a fascinating period piece with some startling qualities. It is combative in its thematic, even for its time.

Violence is presented as a justifiable tool in social change: Frechette buys a gun and attends a campus protest with the expressed purpose of killing a cop (almost 25 years before the rapper Ice-T outraged the establishment with his revenge fantasy “Cop Killer”). Antonioni’s contempt for commercial imperialism is symbolized by the long, ugly parade of advertising billboards and brand-name logos visible through Frechette’s windshield as he drives through Los Angeles.

(Five writers were credited with the final screenplay, including Antonioni, Tonino Guerra, the playwright Sam Shepard, a left-wing journalist and political organizer named Fred Gardner, and Clare Peploe, who was Antonioni’s companion at the time) In his lengthy 1970 review of Zabriskie Point in Rolling Stone, critic John Burks chastised Antonioni for the cliched images of freedom and social oppression in the sequence in which Frechette steals a small private plane and, from his wild-blue perch above Los Angeles, gazes down at the blanket of smog and the rat’s nest of freeways meant to symbolize the soiled heartlessness of consumerism-run-amok. “Corney? You bet your ass it’s corny,” Burks wrote. “Antonioni has constructed his movie of so many lame metaphors and bad puns that it’s staggering.”

But in the introduction to his review - actually one of the kinder published assessments of Zabriskie Point - Burks insisted that while the film was definitely a failure, true, it was not a total loss. “It is seriously flawed, true,” Burks said. “But even the flaws have a grandeur about them.”

The casting of two neophyte actors may have been an attempt on Antonioni’s part to underscore an impression of documentary-style realism in the film. Mark Frechette was reportedly spotted by Antonioni’s scouts at a Boston bus stop yelling:“Motherfucker!” A tense, angry young man, he would later belong to a creepy Boston commune by self-styled guru Mel Lyman. and co-star Daria Halprin was the daughter of avant-garde dancer Ann Halprin.

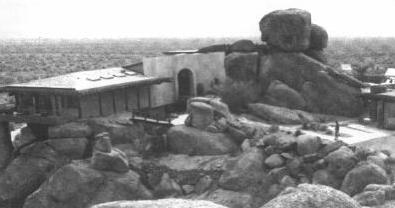

The real star of Zabriskie Point, however, is the desolate, parched, white landscape of Death Valley, in particular the vista from Zabriskie Point, the desert lookout that gives the movie its name and where Frechette and Halprin consummate their brief relationship in a hallucinatory sex scene. It is an eerie, skeletal expanse of stony ridges and dry stream beds, stunning in its ancient, unearthly emptiness. The climatic explosion of the opulent desert retreat belonging to the real estate tycoon played by Rod Taylor - a fit of imaginary vengeance envisioned by Halprin over and over in her mind’s eye after she hears of Frechette’s death at the hands of the L.A. police - is spectacular in its composition and compelling, repetitive effect.

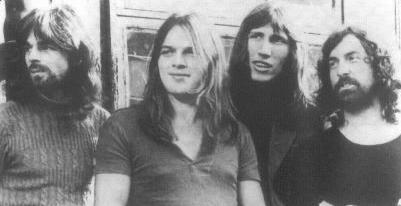

But nothing symbolizes the grand designs Antonioni had for Zabriskie Point - and the lengths to which he would go to achieve his ends - more than the movie’s musical soundtrack, a remarkable melange of abstract sound sculpture, expansive solo-guitar reveries, full-blown psychedelic rock, old-time country ballads, and 1950s jukebox corn. Even Easy Rider, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper’s 1969 smash about two bikers on an ill-fated, cross-country odyssy, featured a relatively orthodox rock soundtrack made up of music (by Jimi Hendrix, The Band, and Steppenwolf, among others) that Fonda pulled from his personal record collection. In Zabriskie Point - a film about the collision of youthful innocence, hardboiled commerce, and social mutiny - bizarre bedfellows such as Pink Floyd, The Grateful Dead, the Eisenhower-era siren Patti Page, the brilliant guitarist John Fahey, the ethnic-folk-rock fusion band Kaleidoscope, and the hillbilly country singer Roscoe Holcomb could all be heard in strange but effective juxtaposition.

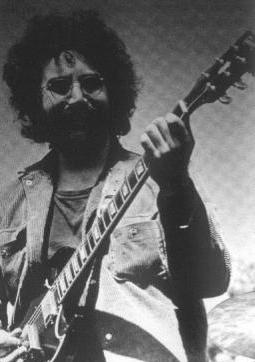

As he did in Blow Up (which boasted a Blue Note-style jazz score by the pianist Herbie Hancock and a fiery cameo by the Yardbirds), Antonioni used music sprangly in Zabriskie Point, with meticulous attention to placement. A spacious instrumental fragment of the Grateful Dead’s “Dark Star” - just over two minutes taken from a 23-minute concert performance on the 1970 album Live/Dead - can be heard as Frechette pilots his stolen plane over L.A.

A short taste of “Sugar Babe” by The Youngbloods, from the band’s 1967 LP Earth Music, plays on a car radio as the lithe and beatiful Halprin first meets Frechette out in the desert. Halprin hears a disc jockey announce Fahey’s “Dance of Death”, a 1964 recording from his Takoma album The Dance of Death & Other Plantation Favorites, following a radio news report of Frechette’s demise.

The radio voiceover was done by Don Hall, a real-life DJ who was holding down the prime-time evening shift at the L.A. underground station KPPC-FM in 1969 when he was approached by Antonioni, through a mutual acquaintance, to work on Zabriskie Point as music coordinator. It was Hall, to a large degree, who brought the catholic vitality of late ‘60s free-form FM radio to bear on the Zabriskie Point score. “There was no idea, when we were doing the flim, that a rock soundtrack meant everything had to be hard, intense, electric music,” says Hall, who was officialy hired by MGM as an A&R executive and company liaison with Antonioni. “I was trying to do a soundtrack using the many different types of music that were being played on FM radio at the time.” Many of the previously recorded pieces heard in Zabriskie Point - “Dark Star”, “Sugar Babe”, Roscoe Holcomb’s jaunty, Appalachian-back-porch rendition of “I Wish I Was A Single Girl Again” - came from Hall’s playlist of personal favorites.

For the desert-jukebox scene, one of his earliest suggestions to Antonioni was to use Patti Page’s sweetly old-fashioned “Tennessee Waltz”, written by country song man Pee Wee King and Redd Stewart in 1948 and recorded by Page two years later by Mercury.

In its original, 11-track vinyl release on the MGM label, the Zabriskie Point soundtrack was a testament to Antonioni’s deep research of and appreciation for pop music, not to mention his excellent taste. Pink Floyd’s “Heart Beat, Pig Meat”, heard during the film’s opening credits as a radical-student meeting is in process, effectively sets the scene’s tone of menace and cross talk with a naked, foreboding pulse-beat and a disruptive sequence of television and radio sound bites. “Come In Number 51, Your Time Is Up” is a cryptically titled remake of the Floyd’s volcanic 1968 B-side “Careful With That Axe, Eugene”. But its bonfire sound - all roaring guitars, crashing drums, and death-throe sceaming - is the perfect complement to the movie’s cataclysmic finish. The extended piece by The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, a solo-guitar improvisation accompanying the love scene, is not just a highlight of the film - Garcia’s fluid melodicism and elegant, crystalline picking make “Love Scene” one of the finest studio performances of his career.

This lavishly expended edition of the previously unissued tracks by Pink Floyd and four exquisite outtakes of Garcia’s “Love Scene” (The final version used in the film is a composite of edits from the full-length improvisations) - documents in even greater depth the vision and labor that went into the movie’s music. In duscussing the cinematography of Zabriskie Point, specifically the use of colors, Antonioni once said:“ You cannot argue that a film is bad but that the color is good or vice versa. The image is a fact, the colors are the story.”

The music created and compiled for Zabriskie Point is an essential part 0f the film’s story - and one of its saving graces. To listen to it now is to wonder again: How did everything else about the movie go so wrong? Chester Crill, the singer, violinist, and keyboard player for Kaleidoscope, remembers all too well the preview screening at which he saw Zabriskie Point. “When it was over,” he says, “there wasn’t a person who left that was looking anyone else in the eye. It was the most embarrassing thing that I’d ever been to. Everybody just slunk away.”

In a 1969 Rolling Stone interview conducted with Antonioni during the shooting of Zabriskie Point, writer Gene Youngblood asked the director about the very spare and particular use of music in his movies. Youngblood cited a quote from the composer Giovanni Fusco, who had worked on Antonioni’s early Italien-language films, including Il Grido (1957), L’Aventura (1960), L’Eclisse (1962), and Il Deserto Rosso (1964). “The first rule for any musician who intends to collaborate with Antonioni,” Fusco said,“is to forget that he is a musician.”

Antonioni was straightforward in his reply:“I don’t like music that makes a commentary on the film. Of course, there will be rock music in the film [Zabriskie Point] as heard on the radio or record players. That’s just natural. Bu I don’t necessarily want a rock score. That would be too easy, too obvious.”

Scoring Zabriskie Point would prove to be anything but easy. And in telling the artists what he wanted - or more importantly, what he didn’t want - Antonioni was anything but obvious.

Born on September 29, 1912, in Ferrara, Italy, Michelangelo Antonioni studied political economy at the University of Bologna and was a film critic before making his debut as a director in the late 1940s. His first productions were short documentaries about Italian culture and society, but they set the tone for much of the work to follow.

During the 1950s Antonioni perfected an unorthodox but enthralling style that emphasized evocative moods and psychological tension over linear narratives. The terse, oblique dialogue and the long, haunting stretches of complete slicence in Blow-Up were classic Antonioni, a reflection of his signature themes: alienation, indecision, the failure of communication. Antonioni was rigorous in his attention to detail, although he could be very elusive in the way he explained himself to other people, including collaborators. “Michelanglo never, never articulated anything that he didn’t have to,” says Harrison Starr, who was the executive producer of Zabriskie Point. And sometimes he didn’t articulate the things he had to. There is a famous story. When he was going to do Blow-Up, Vanessa Redgrave [the movie’s female lead] came to meet with him in a hotel in London. And in his usual way, he told her very little. Finally, she said, “Well, is there a script?” And he said, “Oh, let me see.” He began rummaging around the hotel room. He had notes on a matchbook, notes on hotel stationery. He had notes everywhere. He got them together and handed them to her.

“In fact,” Starr continues,“ he had pages of manuscript. Michelangelo always tried not to define anything until the moment when it would define itself to a certain extent. He had a very delicate touch, and he was very careful about letting things take their place.”

That anecdote explains a great deal about the problems Antonioni had in settling on a final soundtrack for Zabriskie Point and the ultimate, rather motley character of the music. Pink Floyd, John Fahey, and Kaleidoscope were all asked to compose and record extensive scores for the movie. All three submitted new music for the love scene in particular. (It is possible that Jerry Garcia was considered for other work on the film as well.)But in each of those three cases, Antonioni dismissed most of the results as unsatisfactory and confounded the artists to an infuriating degree with his cryptic, sometimes imperious manner.

Antonioni’s first choice to score Zabriski Point - in its entirety - was Pink Floyd. It was, on the face of it, a stange notion. (Although not as strange and intriguing as Don Hall’s first inspiration - the English art-pop band Procol Harum: “I thought of them as Being great for a lot of the desert scenes.”)

The Pink Floyd were a band of former art- and - architecture - school students whose idea of rock ‘n roll revolution had more to do with cruising inner space than brandishing guns in the streets. Distinguished by an understated tension and long stretches of gravity-free improvisation, Pink Floyd’s music was a far cry from the marching-song kicks of the Rolling Stones’ “Street Fighting Man” and the guitar-army aesthetic of explicitly radical U.S. groups such as the MC5.

Yet if they were virtually apolitical, the Floyd were nevertheless a pivotal force in a tight, vibrant English network of underground bands (including the Soft Machine, Hawkwind and the Deviants) that was both inspired by, and a inspiration to, the student uprisings in Europe during the late 1960s. Antonioni was in London in October 1966, filming Blow-Up, when he first saw Pink Floyd at a launch party of Britain’s first underground paper, IT (International Times). By the time he contacted about working on Zabriskie Point, the Floyd already had substantial film experience. With founding singer and guitarist Syd Barrett, the group appeard in Peter Whitebread’s Britain-gone- psychedelic documentary Tonight Let’s All Make Love in London. A realigned Floyd, with guitarist David Gilmour replacing Barrett, had contributed an embryonic version of “Careful With That Axe, Eugene” to Peter Sykes’ 1968 movie “The Committee” and provided the entire soundtrack for director Barbet Schroeder’s 1969 release, “More”. According to Gilmour, Pink Floyd wrote and recorded all of the More music in eight days.

The Floyd spent at least a month in Rome, working 12-hour days unsuccessfully trying to please Antonioni. In Nicholas Schaffner’s 1991 biography of the band, Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey, the group’s bassist Roger Waters is qouted on the experience:“We could have finished the whole thing in about five days…..” But Antonioni “….would listen and go - and I remember he had this terrible twitch - “Eet’s very beautiful, but eet’s too sad,” or “Eet’s too stroong.” It was always something that stopped it being perfect. You’d change whatever was wrong and he’d still be unhappy. It was hell, sheer hell.”

The third Floyd song (in addition to “ Heart Beat, Pig Meat” and “Come In Mumer 51”) to make the soundtrack was “Crumbling Land”, which Gilmour discribed in an interview as “ A kind of country & western number which he [Antonioni] could have gotten done better by any number of American bands. Bu he choose ours - very stange.”

At least 50 minutes of other, presumably unfinished Floyd material, mostly instrumental sketches, were left in the vault. It’s hard to understand what fault Antonioni found in them. The previously unissued pieces in the deluxe edition of the Zabriskie Point soundtrack are not only a vital addition to the official Pink Floyd discography; they are also quite good, even this early blueprint form. The liquid grace of the band’s melodic ideas and performances are a revelatory preview of the lush, refined soundscape on the next two Floyd LP‘s, Atom Heart Mother and Meddle. “Country Song” in particular, is cut from the classic Floyd-ballad mold:

a potent Waters vocal, the stately pacing of drummer Nick Mason, Gilmour’s meaty guitar outbursts. A nice extra touch is the fit of uncharacteristic, honky-tonk piano by Rick Wright under Gilmour’s long climatic solo.

“Unknown Song” (the makeshift titels of the unissued tracks hint at the state in which the band left the music after splitting with Antonioni) is characteristic of the instumental fantasies that typified Floyd’s turn-of-the-70’s shift from the burnt-nerve-ending psychedelia of Syd Barrett to a lusher melodicism. In fact, “Unknown Song” is hardly a song at all. It is a shimmering blend of acoustic strumming., skittish electric picking, and the metallic skidding of Gilmour’s slide guitar. Note, however, the slightcountry-funk undertow of the piano and congas and the way the track goes a bit atonal at the end, as if the guitars and Wright’s piano are working at cross purposes.

Apparently, the Floyd tried damn near everything to come the grips with Antonioni’s vision of the desert sex sequence. At over seven minutes, the Floyd’s “Love Scene-Version 6” is an atypically straightforward - for the Floyd anyway - blues jam, albeit with plenty of room for David Gilmour to show off his silvery, stabbing attack and taut phrasing. “Love Scene-Version 4” is an entirely different approach, a languid exercise in galactic- lounge jazz performed on piano and what sounds like a vibraphone - closer to the Modern Jazz Quartet than A Saucerful of Secrets. An even earlier take, not included here, is a long blue-water stretch of humming keyboards abd guitar dreaming, marked at points by the tidal wash of Mason’s cymbals and moments when Gilmour’s guitar sounds like a flock of agitated seagulls. In the greater context of Pink Floyd’s long career, these newly discovered pieces are transition music. But if they are incomplete, they are certainly not inconsequential. Antonioni’s quality-control instincts definitely failed him when he overlooked one ravishing piece of music from the Floyd’s Rome sessions, a six-minute piano hymn played by Rick Wright for, of all things, the campus riot scene. It’s fascinating to think of how the Floyd were trying to upset, in their way, conventional notions of soundtrack scoring (action equals frantic music; love scene equals soft music). Even more interesting is the fact that the Floyd didn’t waste the piece themselves. “Riot Scene” was later transformed by the band to superbly enriched effect in the song “Us and Them” on 1973’s The Dark Side of the Moon.

As post-production of Zabriskie Point dragged on, Antonioni had John Fahey brought to Rome to create music specifically for the love scene, the lengthy, central dream sequence in which Halprin and Frechette have sex while a corps of rolling, groping couples and threesomes materialize around them at Zabriskie Point and, after consummation, vaporize. (The desert orgie was performed by members of an avant-garde drama troup called the Open Theater, supplemented by extras flown in from La\s Vegas.) In a hilarious and brutally candid account of this Zabriskie Point experience, written as part of a major autobiographical project to be issued by the independent label Drag City, Fahey plainly states his opinion of the footage that Antonioni showd him in Rome:“ a really terrible and long skin flick.” To compound Fahey’s disappointment, Antonioni refused to show him any other parts of the movie.

“Although I ask him, beg him to show me some of the other parts of the film, so I can see what kind of context this footage is in, he will not tell me, or show me this,” Fahey writes. “In fact, he even tells me that he doesn’t want me to know anything about the film other than what I see, and what music I write. Because if I do see other parts, or know anything more about the movie than I already kbow, that could very easely spoil the music that he wants me to write.”

“Let me say this: In all the days, and in all the films for which I have written musical scores, nobody, not one single person, has ever treated me like Antonioni did…Everybody else always showed me anything I wanted to see, answered any questions I asked, in the believe that the more I knew about the movie, the better I would understand what kind of score they wanted.”

Nevertheless, Fahey wrote and recorded a new solo-guitar piece for Antonioni, who expressed great delight with it. But the music was never used. According to Fahey, he and Antonioni got into a heated argument over dinner one night in Rome; Fahey says Antonioni was expounding on the evel and decadence of the United States. The exchange escalated to fisticuffs. “ And,” writes Fahey, “I decked him.” The only John Fahey music to be used in Zabriskie Point was the brief excerpt from “Dance Of Death”.

Jerry Garcia did not go to Rome to record this marvelous guitar fantasia for the love scene. The Greatful Dead guitarist flew alone from San Fransisco to Los Angeles, where he performed on the MGM soundstage; apparently he didn’t even take a roadie. That Garcia was not Antonioni’s first choice for the job is, in retrospect, astonishing. In Garcia, the director found not only a dynamic and sensitive improvisor - a pithy melodicist whose soloing combined a thoughtful folk-blues clarity and a pungent jazz-blues attack shot through with genuinely psychedelic rapture - but also a keen enthusiast of cinema. In the early 1960s Garcia unofficialy attended film classes at Stanford University, where his first wife, Sarah, had been a film student. Garcia was certainly well-versed in Antonioni’s Italian-language work and flattered to be asked to contribute to Zabriskie Point.

“Michelangelo liked the Grateful Dead, and I had a friend who lived across the street from Jerry at the time,” Don Hall recalls. “He talked to him about the movie and we got together. It was almost done as an afterthought. Michelangelo wasn’t even in town when we did the music; he was back in Rome.”

“We went into the large studio at MGM, which they usually used for the symphony orchestras. And Jerry sat there by himself, on a stool, laying it down. They had the love scene on a loop, and he played live while the film was running. He didn’t want to do it away from the film and then cut things in. He played right to any single shot in the scene. That’s why there are certain notes over certain frames, over people moving in the desert. He played right while watching it. It was miraculous - pure genius.”

The session was a productive one. There is more than a half hour of previously unheard, solo Garcia in his collection. And it is essential Garcia. With the Dead, on his solo records, with his various offshoot bands, and in his large body of session work, Garcia was always a sensitive, telepathic player - a master acompanist and generous partner. In these versions of “Love Scene”, he is heard utterly alone, playing with a serene confidence and luminous purity that is unlike anything else in his canon. There are bum notes; he stumbles into the occasional cul-de-sac; but it is live, spontaneous composition, the intimate sound of one of rock’s greatest guitarists caught at the moment of creation. And he was paid well for his labors. At the time when Garcia and the Dead were heavily in debt of their official label, Warner Bros, the MGM check that Garcia received for “Love Scene” was enough to buy him a new house.

The amount of music commissioned, recorded, and rejected for Zabriskie Point could probably fill a separate two-record set. According to group member Chester Crill, Kaleidoscope was the final act brought in to work on the soundtrack. The Los Angeles band had been tapped by Hall, who had known and loved the group during his DJ days. “We were told that they were disappointed in all of the stuff they had from the other people,” Crill recalls. Particularlyfor the little filler material - people walking down the street, turning on a radio, stuff like that. They claimed they didn’t have anything usable.“

Venerated in the underground for their instrumental dexterity and electrifying compounds of acid rock, straight-up country, greasy R&B, and Middle Eastern music, Kaleidoscope had three fine albums out on Epic Records - Side Trips, A Beacon From Mars, and Incredible Kaleidoscope (a fourth, the disappointing Bernice, was already on tape, but not yet released) - when they went to the MGM lot for two weeks of recording for Antonioni. “The reason Don Hall hired us was that we’d done a bunch of stuff like this before,” Crill explains. “We had done films for Encyclopaedia Britannica. We had worked for Disney and Roger Corman. And we could pretty much imitate anybody because of the personnel we had.” With grifted players in the group like multi-instrumentalists David Lindley and Solomon Feldthouse,” says Crill, “we could play 40, 50 instruments between us.”

“Initially, they wanted us to match music with certain sections of the soundtrack, to fix certain parts,” he continues. “But we did 10 original songs too. And for the desert groping scene, we did 10 or 12 takes. It was mystifying, to say the least, as to what they wanted.” According to Don Hall, Kaleidoscope worked in a small Los Angeles studio next door to the room where schmaltzmeister Lawrence Welk recorded overdubs for his weekly television show. At those Kaleidoscope sessions where Antonioni was present, the director said little or nothing abou what he thought of the music or what he wanted for the band.

“He seemed totally flipped,” Crill says. “At the time, I had a red violin and he was crazy about it. ‘Do you like the music?’ I asked him. He said, ‘No, but the red violin was great.’ ” In the end, Antonioni only used two short, rather conventional Kaleidoscope pieces. The bouncy country song, “Brother Mary”, was played mostly by Lindley and sung by Jeff Kaplan, who had recently joined the band. “Mickey’s Tune” was an instrumental rereading of the Buck Owens song “Hello Trouble” they’d previously covered on a 1968 single.

“The funny thing is that when they asked us to do the project, by the time they got to us, they said:“Well, we really don’t have much money left in the budget to give you guys”, Crill says, laughing. “In fact, it was the most money we ever made.”

Some music used in the film was left of the soundtrack album. One such piece - performed by MEV (Musica Electronica Viva), a collective of American experimental composers based in Rome and specializing in live electronic improvisation - was a segment of avant-junkyard clatter heard in the movie as Frechette drives his truck through the heart of L.A.'s industrial wasteland.

(Members of the ensemble included noted contemporary musicians Alvin Curran, Frederic Rzewski, and Richard Teitelbaum) Licensing restrictions accounted for The Rolling Stones’ absence from the record. The aching country blues “You got the Silver”, sung by Keith Richards and taken from the Stones’ 1969 album Let It Bleed, momentarily surfaces in the movie as Halprin hits the road, fidling with the radio in her car, after Frechette flies back to L.A. to return the stolen plane.

Ironically, one of the most expensive pieces of music in the film and on the record was “Tennessee Waltz”. The state of

Tennessee had passed legislation declaring “Tennessee Waltz” theofficial state song; and they were extremely reluctant to allow the tune to be used in a film associated with drugs, free sex, and student revolution. In the end, after long, tough negotiations with the Tennessee government, MGM - which had already pressured Hall (to no avail) to use a number from the label’s extensive Hank Williams catalog - paid dearly for the use of the song. “It wouldn’t have hurt to use a Hank Williams song,” Hall admits. “But I’d played the Patti Page record for Michelangelo and he loved it. And he was not going to change his mind.”

The depths to which relations between Antonioni and MGM plummeted as Zabriskie Point lurched to completion can be measured by the last-minute inclusion - behind Antonioni’s back - of Roy Orbison’s “So Young” at the very end of the film, as Halprin drives off after the explosion sequence. Harrison Starr claims that MGM president James Aubry and Mike Curb, the young head of the company’s record division, devised a plan to stick an additionel song in the movie - probably because, after spending so much money on the project, they discovered there were no MGM artists represented on the soundtrack. Orbison was an inappropriate choice, however; with his longtime collaborator Bill Dees, the great melodramatic singer wrote, by his standards, a colorless ballad completely out of sync with the sound, look , and intent of Zabriskie Point.

Nevertheless, “So Young” was literally pasted on to the picture, probably after Antonioni delivered what he believed to be the completed product. The song is not even listed with the rest of the musical performances in the movie’s opening credits. “I didn’t know anything about that song,” says Hall, “until I went to one of the first actual public showings of the film, at a theater in Westwood in Los Angeles. At the end of the movie, we had the explosion music, which I thought was quite effective. Then, all of a sudden, there was a freeze frame - I went ‘What the Hell?’ - and this droning sound [began coming out] of the speakers. I love Roy Orbison. But my God, it’s a horrible song.” Oblivious to the banality of Orbison’s performance and the song’s incongruous place in the film, MGM released “So Young” as a single in April 1970; it was even given the subtitle “Love Theme from Zabriskie Point”. But it did not appear on the soundtrack LP. (Appropriate to Antonioni’s original desings, it is not included in this edition.) Not many people noticed. In one more crushing disappointment for Antonioni, the Zabriskie Point album never appeared on the Billboard charts.

It would be five years before Antonioni fully recovered from the disastrous experience of Zabriskie Point. He finally concluded his MGM contract in 1975 with The Passenger, an existential thriller starring Jack Nicholson that restored his critical standing. (Iggy Pop named a song on his 1977 album Lust For Life after the film; and in 1995 U2 and Brian Eno released a soundtrack-music project under the alias Passengers.)

Ironically, Mark Frechette died in 1975 under suspicious circumstances in a Massachusetts prison, where he was serving a 6-to-15 year sentence for his participation in a 1973 bank robbery in Boston in which two men were killed. He was found in the prison’s recreation room asphyxiated, pinned to the ground by a set of barbells perched on his throat. Only 27 at the time of his death, Frechette had gone from playing an angry young man with a gun in Zabriskie Point to actually wielding a pistol in a bungled real-life stickup that he characterized as a political act after his arrest: “It [the robbery] would be like a direct attack on everything that is choking this country to death.” (Daria Halprin, who had an affair with Frechette during the production of Zabriskie Point, later married - and divorced - Dennis Hopper)

Antonioni has continued to make movies, despite a 1985 stroke that has impaired his ability to speak. He has also lived to see the same nation that once outraged him, and which in turn rejected his vision of social revolution, pay him one of its highest artistic compliments. In 1995 the director was given an Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Zabriskie Point remains an important part of that life, an epic work of ambition symbolizing the spirit of its time, even if the movie does not effectively capture it. Antonioni himself may have suspected that capturing the energy, optimism, and desperation of such a volatile era in a single motion picture was a difficult, even hopeless task. “What’s different about this revolutionary generation is not what the young people want - freedom. Everybody always has wanted that,” Antonioni said in the 1969 Rolling Stone interview. “What’s different is the way they go after it. It’s a matter of practical application. They know what they want, but they don’t know exactly how to reach for it.”

Zabriskie Point is not a historic film. But it is a fascinating window into a pivotal chapter of American political and cultural history. So is this music.

Auteur de la page :

paxi83,

manu.